Sue Harvey, Partner at Campbell Tickell, explores reclassification of Ireland’s approved housing bodies.

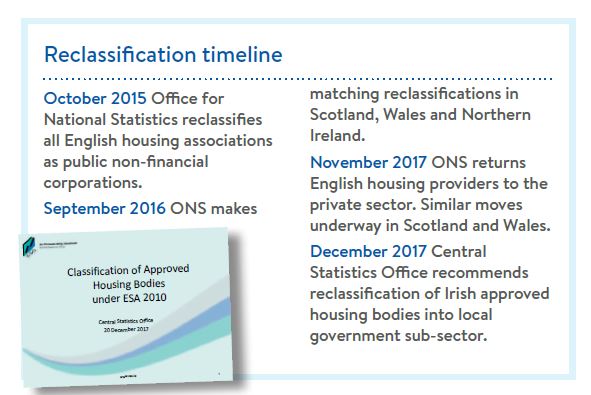

Do you remember where you were on Halloween 2015? That was the day the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reclassified all English housing associations from private non-financial corporations to public non-financial corporations (PNFCs) in the National Accounts. The ONS was on a roll: less than a year later it followed up this decision with matching rulings for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (see box: Reclassification).

The key impact was to bring onto the public sector balance sheet £66 billion of housing association debt, along with the associated assets. In all four jurisdictions the key triggers for reclassification were seen to be central or local government control of housing associations.

The key impact was to bring onto the public sector balance sheet £66 billion of housing association debt, along with the associated assets. In all four jurisdictions the key triggers for reclassification were seen to be central or local government control of housing associations.

Financial impact

What initially appeared to be a dry and statistical matter caused consternation when it became apparent the moves could seriously limit the amount of borrowing available for investment in social

housing, together with other changes limiting the autonomy of housing providers. Trick or treat? In the case of the English associations, relatively swift action by the government in introducing a range of deregulatory measures into law saw the sector reclassified back to the private sector within two years. Deregulatory measures to enable similar reclassification in Scotland and Wales are passing through the respective devolved legislative bodies.

Progress in Northern Ireland has been delayed by the lack of a functioning government since March 2017, but the intent remains to achieve a reclassification to the private sector here too. It is not just the UK’s private social housing providers that have been affected by the statisticians and their new-found interest in our sector.

The Irish experience

Just before Christmas the Republic of Ireland’s Central Statistics Office (CSO) announced that it will recommend to Eurostat (the EU body with the final say on these matters) that 14 of the largest Approved Housing Bodies (AHBs, the Irish equivalent of housing associations) should be reclassified into the local government sub-sector from their current classification as non-profit institutions serving households.

The Irish social housing sector is very different from that in the UK. There are approximately 520 AHBs managing around 27,000 homes but just 18 of those have stock of more than 300 homes. These ‘Tier 3’ bodies account for 80% of the sector’s stock. The largest, Clúid Housing, manages approximately 6,000 homes. Many of the smaller organisations are single-property organisations, often ‘staffed’ entirely by volunteers and funded through charitable donations.

Another difference with the UK is that more than 99% of the capital funding for Tier 3 AHBs has come from the government. Contrast this with grant making up just 33% of the historic funding for the top 300 English associations at the time of the ONS decision (the remainder being private debt and retained profits). This is the key driver of CSO’s decision and it is difficult to envisage it being reversed in the short-term.

Impact of reclassification

The consequences for the reclassified AHBs are wide-ranging, will develop over time and many will hinge on the ‘destination classification’. There are crucial differences between being part of local government versus being considered PNFCs. The possible longer-term consequences include:

- the assets being necessarily aligned with the debt, and hence ‘owned’ by the relevant central government department or local authority; being subject to public sector spending controls which can be administratively onerous, and which could include headcount freezes, permissions being required for capital expenditure, salary restrictions and/or redundancy limitations;

- a requirement to obtain annual business plan approval from the relevant government department or local authority, which in turn can present government with the opportunity to control strategy, policy and capital projects;

- freedom to borrow new funds in own name being replaced by the need to apply to use government general borrowings, which in turn are subject to the restraints imposed by the Eurozone fiscal rules. This could severely constrain the capacity of AHBs to fulfil their development ambitions or to contribute to stock transfer plans;

- accounting policies and audit arrangements needing to align with those of the public sector, including coming within the remit of the comptroller and auditor general.

Campbell Tickell is supporting parts of the sector to press the arguments, and the next move for Irish AHBs is in the hands of Eurostat. The Irish government expects AHBs to deliver a significant share of their ambitions to build 47,000 social homes by 2021. So has this target been put in jeopardy by the proposed reclassification? Scary indeed.

To discuss the issues raised in this article, contact sue.harvey@campbelltickell.com

This article also appears in CT Brief, Issue 34