Image: Istock

Charity governance in a changing world

Reflections on recent revisions to the Charity Governance Code

GOVERNANCE

Matthew McClelland

Director, Campbell Tickell

Radojka Miljevic

Independent Chair of the Charity Governance Code Steering Group, and former partner at Campbell Tickell

Issue 82 | February 2026

Reflecting on the Charity Governance Code revised in November 2025, Radojka Miljevic – Independent Chair of the Charity Governance Code Steering Group and a former partner at Campbell Tickell – discusses with Matthew McClelland, Director at Campbell Tickell, how charity governance has changed, the key updates to the Code, what distinguishes effective boards, and the challenges facing trustees today.

Matthew McClelland: Looking back over the past 20 years, how has charity governance changed?

Radojka Miljevic: One of the biggest changes has been the professionalisation of governance. Trustees being unpaid volunteers is no longer seen as a sufficient defence when things go wrong. Expectations of boards have risen significantly, in line with other sectors.

This brings both opportunities and tensions. Charities are driven by passion and commitment, but that now needs to be combined with strategic competence and a clearer understanding of how boards drive change. At the same time, the sector is hugely diverse. Governance looks very different in a small charity with a handful of staff compared with a large, complex organisation.

Regulation has also increased, and with it a sense that governance can feel burdensome. Roles such as heads of governance or legal counsel have become more prominent, especially in larger charities. Alongside this, high-profile failures around safeguarding, solvency, fraud or organisational culture have created anxiety for trustees. Many now worry about personal accountability in a way that wasn’t as evident 20 years ago.

That said, there have been real improvements. Boards are generally smaller and more focused, trustee tenure is better managed, and there is greater attention to board composition, skills, conduct of meetings and quality of papers. Overall, there is a much clearer sector-wide understanding of what good governance looks like.

What makes an excellent charity board?

It’s not just about having impressive individuals around the table. I’ve seen boards full of highly accomplished people that still weren’t effective.

What really matters is what I sometimes call ‘NED muscle’ but which applies to Trustees as well as NEDs [non-executive directors]: the ability to ask thoughtful, open questions rather than directive ones; to use experience generously; to be curious rather than defensive; and to admit when you don’t know something. That takes confidence and self-awareness.

At a collective level, excellent boards have psychological safety. They can hold challenging debates without them becoming personal or destructive. That requires trust, consistency and patience in working through differences until views coalesce into a decision.

Strong boards are also curious. They want to learn what good looks like elsewhere, to reflect on their own performance, and to invest time in understanding how they add value. They don’t see reflection as a ‘soft’ activity, but as central to effectiveness.

Shared language is critical too. Boards and executives often use the same words: ‘strategy’, ‘risk’, ‘assurance’, but mean different things. Effective governance depends on aligning those meanings.

Finally, the relationship between the chair and the CEO is pivotal. That relationship sets the tone for the whole organisation. Constructive tension, mutual respect and clarity about roles are essential. If that axis isn’t working well, board effectiveness will suffer.

“What really matters is... the ability to ask thoughtful, open questions rather than directive ones; to use experience generously; to be curious rather than defensive; and to admit when you don’t know something.”

“The last major revision was in 2017, and the world has changed a great deal since then.”

What prompted the latest revision of the Charity Governance Code?

The last major revision was in 2017, and the world has changed a great deal since then. We’ve seen safeguarding failures, the pandemic, economic instability, increased focus on equality and inclusion, and a much more polarised social and political environment.

While a governance Code can’t respond to specific events, it does need to reflect the social context in which charities operate. As a steering group, we were conscious of balancing enduring principles of good governance with the realities charities now face.

We didn’t begin with a fixed agenda of issues to address. Instead, we undertook a wide consultation of around 500 responses which helped us understand where the Code needed to be clearer, more accessible or more challenging.

How is the new Code structured differently?

We moved from having separate versions for large and small charities to a single, unified Code. The sector is diverse, but we felt it was important to articulate a shared vision of good governance that applies to all charities.

The heart of the Code is a short set of principles and outcomes, set out in under 1,000 words, that describe what good governance looks and feels like. These outcomes are universal.

Everything else is supportive guidance, not prescription. Boards are encouraged to exercise judgement and adapt the suggestions to their own context. We deliberately moved away from long, detailed recommended practice sections that could feel inaccessible or overly prescriptive.

A significant addition is a clearer focus on behaviours, i.e. what is expected of trustees, chairs, and boards collectively. Much of governance is relational, and previous codes didn’t always address that strongly enough.

What changed within the principles themselves?

All the principles were revisited, even where the names stayed the same.

We strengthened the foundation principle, which had previously felt underplayed, and placed more emphasis on organisational purpose, impact and looking to the future. Leadership now has a stronger focus on values and behaviours and recognises the role of senior staff.

We introduced a new ethics and culture principle, combining elements of the former integrity and openness principles, to prompt deeper thinking about behaviour and values, not just compliance.

Decision-making was separated out more clearly from risk and control, recognising how central good decision-making is. Resource stewardship was broadened beyond finance to include people and organisational capacity.

The EDI [equality, diversity and inclusion] principle was revised to be less prescriptive while still foregrounding equity and power, issues that are fundamental to the charitable sector’s role in society.

What are the biggest governance challenges facing boards over the next few years?

First, societal polarisation. Many charities are dealing with contentious issues, increased hostility and, in some cases, threats to staff and volunteers. Boards need to think seriously about how they protect people as well as how they position the organisation.

Second, technological change. Cyber risk, data protection and digital transformation are real vulnerabilities for charities, particularly where there has been underinvestment in infrastructure.

Third, equality, diversity and inclusion remains a major challenge. In some environments, the value of EDI is being questioned or contested. I think it’s vital that charities continue to own this agenda and connect it clearly to purpose and impact.

“Cyber risk, data protection and digital transformation are real vulnerabilities for charities, particularly where there has been underinvestment in infrastructure.”

What advice would you give to new trustees?

Do your due diligence before you join. Read the annual report and accounts, understand the charity’s work, and treat recruitment as a two-way process.

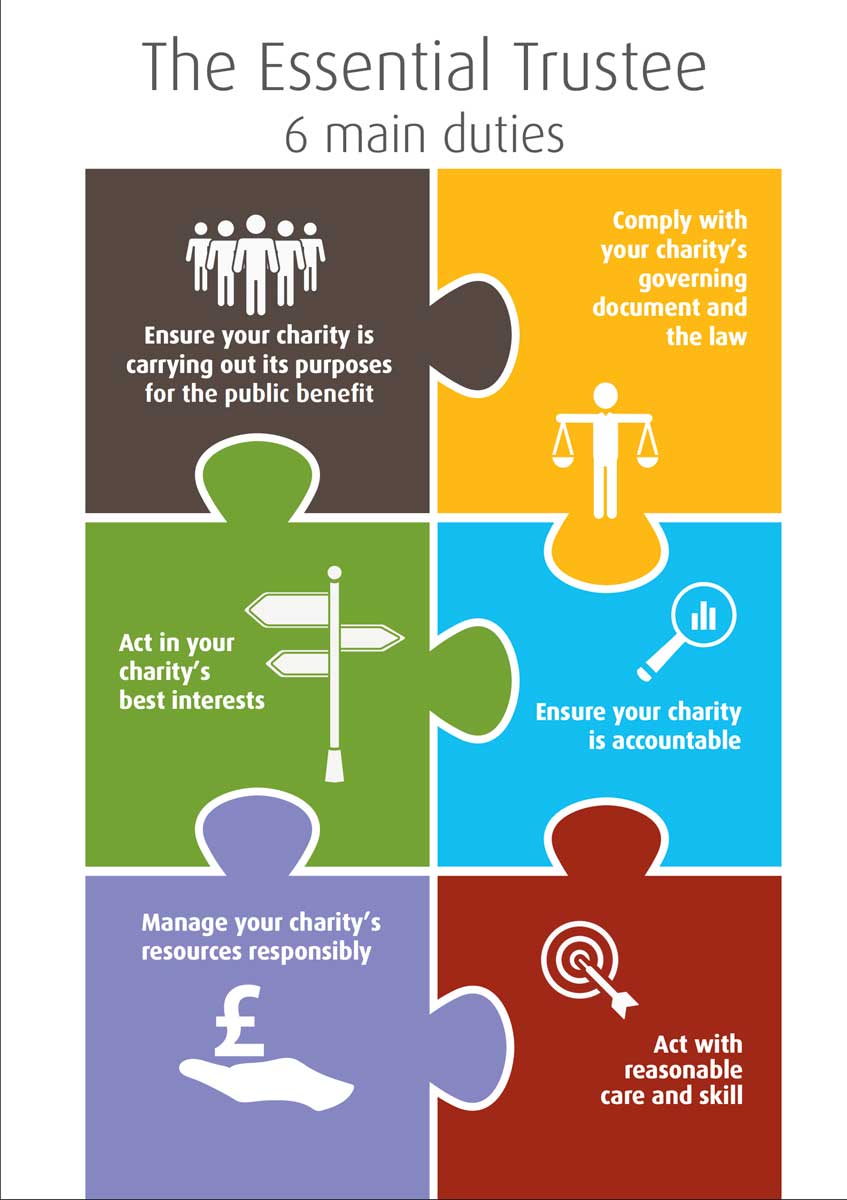

Once appointed, take the role seriously. Read key guidance such as The Essential Trustee, understand the governing document, and be clear about expectations, time commitment and conduct.

Build an early relationship with the chair and CEO. Ask what good looks like, why you were appointed, and how feedback works.

Stay curious and keep learning. Engage with sector bodies, follow regulatory updates, and try to understand the organisation beyond the boardroom through visits, events or contact with service users where appropriate.

Trusteeship is a privilege. It requires commitment of both head and heart, and it deserves to be approached with professionalism as well as passion.